Where our troubles are all the same,

but they're always glad you came

This essay originally appeared in the catalog essay for an exhibition titled ___place in 2009 at the Columbia College Chicago A+D Gallery. It is reproduced with permission of the author. ______________________________________

Not so long ago, I was on my way home when I took a wrong turn. I had been absentminded, so my misstep put me in an unfortunate predicament: the surroundings were unfamiliar and I no longer knew where I was. What is more, it was unclear which direction I was facing, and I could not retrace my steps.

|

As I remember it, this moment of displacement brought with it an experience of cold anxiety and embarrassment (you see, more than once I’ve claimed to have a good sense of direction, and this state of affairs offered too many reasons to dispute that claim). Surprisingly, the confusion also included a jumpy excitement. My imagination raced. This could be anyplace. Who lurked in those nearby shadows? What was that sound? How would I find my way? My anxiety lasted for about as long as it took me to find the mobile device in my pocket (the salesperson assured me it was worth its price – it was enabled with a “GPS” system). Once I figured out how the thing worked, it not only charted the lay of the land, it also showed “me” on a digital map. My imagination crashed. As the handheld guided me towards my destination, any adventurous excitement faded – my place was just ahead, on the left.

Imaginations have long been captured by sight of unfamiliar places from either long ago or far, far away; most especially when the places were far away long ago. Distant places and mysterious spaces have been topics of art since ancient times. In turn, artworks have long seemed to offer their viewers visions of dated images and even older worlds. New places and even newer images have found their way into recent art as well – one critic has recently argued that narratives of place are central to the very definition of contemporary art.1 However, offbeat places and dissonant eras have produced multifarious pictures, which is why historical accounts are not just descriptions of spaces and times, they are also representations of events and practices.2

The idea of place is as central to art now as it was in ancient times, which suggests the notion has a strange, timely character. Specific notions of a place are straightforward enough, but what is it about the concept of “place” itself that is peculiarly exiting? What does it mean for people and things to be in place? How do people use place right now? Is it different from how place worked before? What, if any, is the difference between place and space? These sort of philosophical questions are tricky at best. This much is certain: the question of place is intimately connected to seeing in a special way. After all, looking at a place is not the same as looking in a place. This essay thinks through some of these issues. It is an attempt to sketch out some questions coming from a specific space – the A+D Gallery’s exhibition ___place. This is an exhibition of four artists who produce works that maintain intimate relationships to place.

Take, for example, the misplacement in Abnormal Formal, an artwork by Anna Kunz. This installation of found materials seems to trouble the distinction between something in place and something out of place. In this artwork, viewers are invited to be part of the work, both physically and conceptually. The placement of the found objects Kunz assembles and paints are visible from the storefront window of the gallery, which allows the images produced by this work to spill out beyond architectural boundaries. Kunz troubles divisions between the space outside and the place inside, but she also confounds conventional ideas about painting. In Abnormal Formal colorful paint interacts with the gallery’s architectural space and three-dimensional volumes to generate an absorbing, immersive environment. It is as if items of the everyday world have chosen to assemble in one place and communicate in languages of color and composition.

Composition relates to the everyday use of place. It may also seem to make the meaning of “place” more clear: as a noun, place is either unbounded space or a room, but either way, it is an available space that can be arranged and occupied. This definition suggests that a space becomes a place only once objects have been moved in. To notice this is to bring time into the place-making process – how long does it take for a space to become a place?

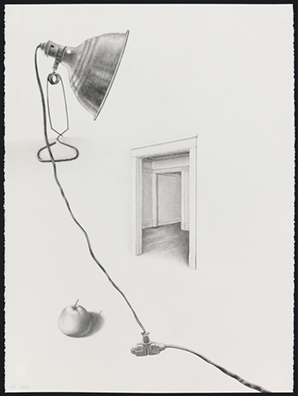

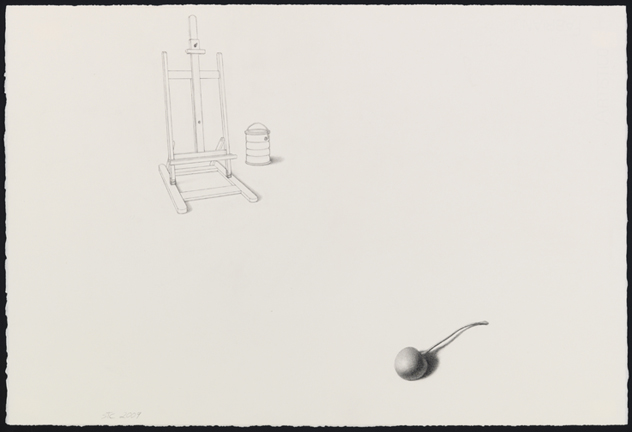

Place refers to continuous or unbounded extension in every direction, but it has a strange relationship to time. Steven Carrelli’s artwork seems to bring time and place together. The objects in Carrelli’s carefully rendered graphite drawings work in concert to activate their surroundings. The Space Between is an efficient example. In this drawing three objects work in concert to declare both tense ephemerality and fragmented density. Look at the contour drawing of the easel and barrel together in the background. Carrelli’s precise pencil marks activate the pristine area in which they are placed. In a similar way, a foreground is activated by a solitary cherry rendered in volumizing chiaroscuro. These three forms work in concert to emplace a distancing mid-ground. Carrelli’s drawings are quietly historical. They invent space through illusionistic perspective, but they also invent time through reference to past eras (the European Middle Ages and Renaissance) and far places (Italy). In these drawings the past is recalled and spaces are revisited – place becomes an active verb.

The active use of place uncovers its active character. Whenever a thing is placed, that thing occupies a particular position – it is stationed in place, that is, in a particular state or relation to other things or ideas. Artists have used specific places as active sites – locations in which new roles may be performed. In performances, place functions more like a scene. So, what is the difference between space and place? One quick distinction might be that place is a specific, definite location, but space is less stable, more variable and active, a sort of practiced place. For example this seems to work well if we were to choose to align space with itineraries and place with maps. As anyone who has encountered science fiction knows, space seems more abstract – a journey into “outer place” just doesn’t have the same ring to it as a journey to “outer space.”3

Look, for example, at Spacesuit by Betsy Odom. Odom is conscious of paradoxes that come out of small movements of place, space and time. Spacesuit occupies a domain between craft and sculpture, functionality and fecklessness. The soft sculpture points towards markers of identity and belonging, zones of competence and areas of bravado. Spacesuit is calico, bright pastels and fluorescent plaids interrupt what would be a homogenous white. There is an orange ring around the collar, but without a helmet that would obscure the view of the suit’s wearer, whomever is to live out the fantasy. Space travel has long been the stuff of imagination – they are fantasies woven with concepts of conquest, nationalism, desire, even gender and sexuality. The colors of this suit, then, remind viewers that “fluorescent” means to thrive and produce, even if, historically, advances in technology demarcated boundaries that displaced, misplaced and alienated many people. Spacesuit works to bring its viewers together – or at least remind the viewer that everyday life connects us in ways that coded boundaries of gender and sexuality cannot describe.

So just how are we to describe the places of everyday life? Where and how are such daily events placed? The difference between the where and the how is pronounced in English, but in other languages the difference is slight between the place (topos) in which things happen and the manner (tropos) in which they go about happening. Such overlap is evident in the collaborative process of topography, the practice of describing the features of a region or locality.4 In topography problems of place are endemic – how is the “local” to be distinguished from the “exotic” or unfamiliar? When do “we” become parts of places? How and when do things become places?

These sorts of questions come up when looking at Michael K. Paxton’s drawings on unstretched canvas. Paxton’s work engulfs its viewer in abstract views of mountains and islands. The forms are rendered in vigorous gestures that fade into the backgrounds and foregrounds of their scenes. The panoramic pictures seem to vibrate with fluctuating marks that remind the spectator what a challenge it is to render place – in or out of space and time. These scenes tell tales of place and displacement at once, because the viewer has a difficult time locating a stable position from which to look. On one hand, a view from too close forfeits general comprehension – on the other hand, a move too far away loses a sense of the particular. The pictures are, therefore, puzzles of aspect and ratio. The vistas Paxton produces specifically for the space of A+D Gallery are enveloping, large-scale tableaus – they invite perceptual paradox and end up referring to the very drama of vision itself.

Dramas of the visual world are ongoing. For example, recently a network television show has (again) capitalized on the histrionics with a familiar storyline: a group of characters are stranded, displaced on a deserted island. They are faced with no choice but to look to their inner strength in order to survive. In life off-screen, tales of place and misplacement may be less melodramatic, but they are no less sensational. Space and time are still unsettled affairs, and even if digital devices offer directions, navigating the wilderness of the visual world requires more inner strength than ever before. The artworks presented here offer new places that might help all of us navigate in a tumultuous world.

______________________________________

Copyright Raél Jero Salley, 2009

Raél Jero Salley is an artist, cultural theorist and art historian. He holds degrees from The Rhode Island School of Design (BFA), The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (MFA), and The University of Chicago (PhD). His research interests include modern and contemporary art and visual culture, with a focus on Blackness and African Diaspora.

______________________________________

1 Nikos Pastergiadis “Spatial Aesthetic: Rethinking the Contemporary” in Antinomies of Art and Culture edited by Terry Smith, Okwui Enwezor, and Nancy Condee (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008), 363

2 Landscape and Power edited by W.J.T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), xi

3 Mitchell quotes Michel de Certeau in Landscape and Power edited by W.J.T. Mitchell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), xi; See also Michel de Certeau The Practice of Everyday Life translated by Steven F. Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984)

4 Papastergiadis 374